John Dee’s America, by Jim Egan. Cosmopolite Press, 2015. Nonfiction, 584 pages. $19.95.

As Queen Elizabeth’s advisor, John Dee’s concept of North America was purely speculative – he never set foot on the continent. He referred to it as “Meta Incognito” in legal documents (“Atlantis” on his own maps), and he proposed that it would be the home of a new British Empire, which would guarantee religious freedom for all. With the blessing of the Queen and the help of her wealthy aristocrats, Dee’s colonization effort of 1583 was launched just before the ill-fated Roanoke colony – and the first experiment ended even more swiftly than the latter.

Such are the foundations of John Dee’s America, a graphic dissertation on the role of England’s greatest conjuror in the pre-production and eventual establishment of colonial America. Author Jim Egan takes every effort to provide context for Dee’s American vision, reaching not just through the annals of history for dates and names, but by correlating the contents of Dee’s massive library, unpacking the philosophy of 15th century English symbolic language, and modernizing & annotating his primary sources to provide abundant material for the reader to explore. Egan doesn’t just hand over mackerels; through simple explications of geometry, cartography, and astronomy, he teaches his readers to fish through the waters of our past in order to draw their own conclusions.

That isn’t to say that Egan doesn’t make various conjectures of his own. Although John Dee’s America serves on one hand as a comprehensive guide to the 1583 colonization effort, & as a focalization of all of the available research available on the subject, Egan also pursues an archeo-political objective in his book: providing an explanation for the origins of the mysterious Newport Tower, a massive ruin that stands in the town of Newport, Rhode Island (which is in the approximate location of John Dee’s proposed colony). This volume is a single fragment of Egan’s sprawling 12 (13?) book thesis regarding John Dee and the Newport Tower. If Egan’s hypothesis is correct, that would make the tower the oldest standing colonial structure in North America, and the very first building erected by the British Empire. Egan is certainly convinced of the matter, and opened The Newport Tower Museum just a few steps away from the ruin itself, vying for a UNESCO Heritage seal of approval.

It’s a fascinating idea that only holds as much water as the historical record supports; there are still some holes, as Dee cannot be directly connected to the Tower by any primary sources. I personally think there’s some hope that clarifying documents lie dormant in British royal archives, in whatever State papers remain of the first Elizabeth regime; the extent of John Dee’s role in American colonization was unknown, for example, until as recently as 1976, when his 4 Volume “Limits of the British Empire” was rediscovered in the British Library (written in 1577 – 1578). In total, he wrote eight volumes for Queen Elizabeth on the subject of British expansion (Rare and General Memorials contains the other four), some excerpts of which are included in John Dee’s America. Of these eight volumes, one still remains missing, likely suppressed by Elizabeth; the majority of the colonization effort of 1583 was conducted in secret, so as not to rile the Spanish. If Dee did construct the Newport Tower (as a means to establish ownership of the land, and to greet the incoming colonists), he did so with the blessing of the Queen and her company – and somebody must have paid for it all. Although Egan’s research hasn’t conclusively proved anything, he’s pieced together a story within a story that has tremendous implications.

Any building records of the Tower that might have existed during the Colonial era, meanwhile, would have been obliterated during the American Revolution, when the British occupied Newport. John Dee’s America spends its second half examining post-Elizabethan colonial Newport, and the first known owner of the Tower, Benedict Arnold (not the traitor, his great-great grandfather), who actualized Dee’s vision of religious freedom in his colony, Rhode Island. Arnold is an interesting figure in his own right; the first governor of Rhode Island, who married into British royal blood and passionately fought for American civil liberties, and the separation of church and state, while accruing as much land and power as he could. Amidst the drama of early colonial activity, with its land disputes, religious factions and various rebellions feature into his life and times, Egan always ties his historical fragments back to his thesis; Dee’s vision, the looming Tower, and what that Tower signified to to those early colonists who adopted it.

As Egan points out in the book, John Dee understood the urgency of religious freedom for all. He had been imprisoned as a young man, accused of conjuration and heresy by Queen Mary’s Catholic inquisition. Dee was clever enough to survive the ordeal, but all around him, his fellows were being burned at the stake, flayed in dungeons, & hung from the gallows. When his beloved Queen Elizabeth rose to power, the circumstances reversed, and it was the Catholics turn to be persecuted. Dee wanted to end the cycle of violence and distrust, and proposed that all of Elizabeth’s colonists be given freedom to practice their own faith. In the New World, Dee envisioned a New Jerusalem, where all men and women, Protestant and Catholic and indigenous folk alike, would be able to live in a universal harmony.

It’s particularly fitting, with that in mind, that Dee’s agent of conquest, Humphrey Gilbert, died in a shipwreck reportedly crying out a reference from Thomas Moore’s Utopia. “We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!” He was sent with five ships to establish Dee’s colony at Newport; only one ship survived their ordeals, and returned to England. As of this writing, no Utopian societies have yet been successfully implemented.

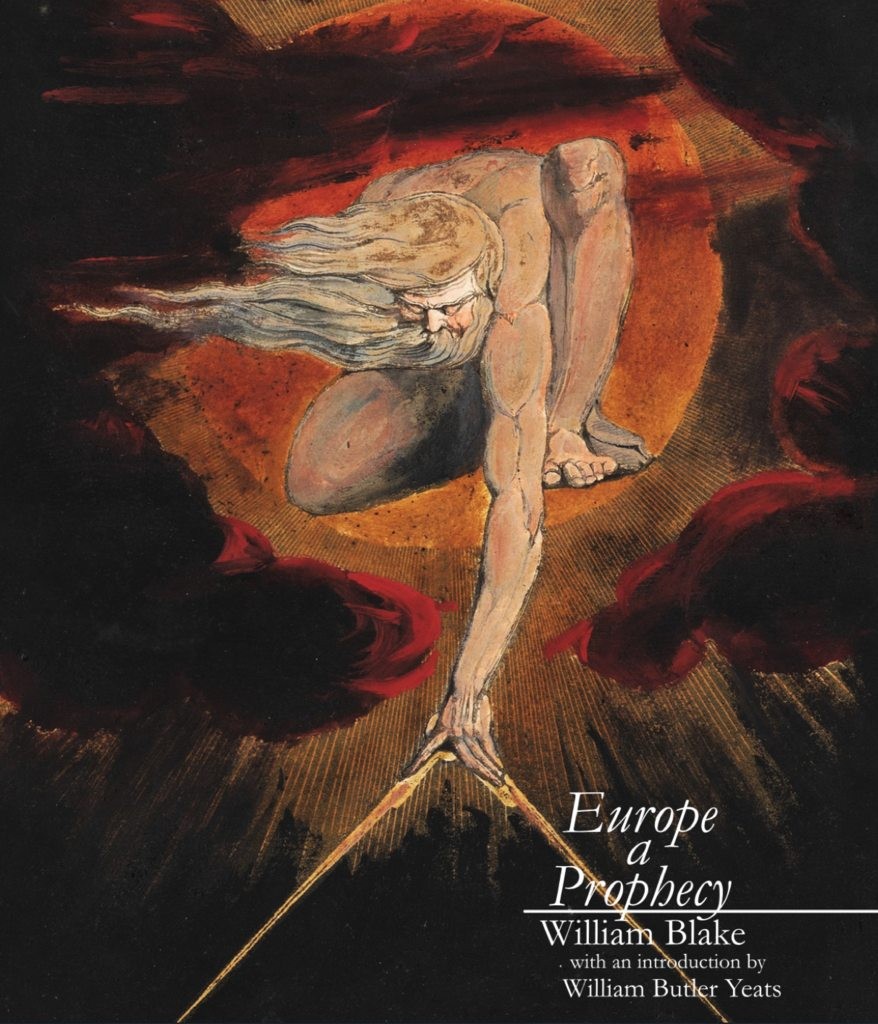

Egan’s illustrations that abound throughout the pages add a certain charm to the generally despicable cast of scheming English nobles – his characters have a crude, friendly Quentin Blake quality (see the cover, above), and their portraits become recurring iconography of later diagrams that help distill information. Small illustrations of scenes – such as the death of Gilbert, or the Tower being blown up in the Revolutionary War – embellish the dramatic moments more than the text itself, which retains a calm, fairly neutral tone through the turbulent epochs explored.

Where Egan’s work really shines is in the decipherment of puzzles. For the frontispiece to General and Rare Memorials, John Dee illustrated the Hieroglyphicon Britanicon, an enigmatic illustration intended to persuade Queen Elizabeth to conquer. Egan delineates the symbolic components that are not immediately obvious to a casual reader in the 21st Century, and further endeavors to solve the riddles Dee implanted (a latin banner above the illustration reads, “More is hidden than out in the open”). I don’t know if I am convinced of all of Egan’s solutions to the riddles (does a crook in an arm the letter “D” make?), but his identification of Archangel Michael’s role in the meta-colonial tableau is a remarkable association, and I wonder if Egan wasn’t the first person in 400+ years to figure out Dee’s clue on his own.

John Dee’s America is a massive endeavor, and, though written simply enough, the tale becomes quite convoluted; it’s crafted from so many sources and narratives, and some of the connections feel tenuous. Egan includes a lot of conjectured material, such as speculating on the significance of names, and the potential motivations of men whose true motivations we simply cannot know. Did Benedict Arnold really consider himself to be the King Arthur of America? Did he consider Newport to be his Camelot? Although some of Egan’s ideas tend to reach, he makes it quite clear what is theory and what is not, and how he’s reached any given hypothesis; and in writing about young Benedict Arnold’s homeland near ruins of Arthurian renown, Egan explores large vistas of myth and legend that intersect with the origins of America in new and curious ways.

By page 453, Egan presents his Grand Visual Summary of the book, a ten page graphic that breaks down the narrative by location, characters, influences, and recurring symbolism. It’s a a huge boon to even the most diligent reader; there are many threads to be connected, and you probably haven’t been taking notes. The subsequent appendix provides material from another of Egan’s books, Elizabethan America, the John Dee Tower of 1583, which furthers Egan’s mission to prove the theory that John Dee did, in fact, design the Newport Tower. Egan looks at the tower from a multi-disciplined approach, combining history with astronomy, photography and an interpretation of Dee’s most cryptic work: the notoriously enigmatic Monas Hieroglyphica, which Egan has approaches with even more scrutiny than the Hieroglyphica Britanica.

There are no half measures in John Dee’s America; it is a massive volume. Still, it is delivered with a clarity of vision that allows a reader to open to virtually any page, glance over the graphics, and dive into any fragment. Jim Egan is a diligent guide on this journey, timing his strides to ensure that all paths are walked, and no stone left unturned. The Tudor dynasty, phantom islands, Christian cults and a multiplicity of cryptograms abound in these pages. As the pieces come together, the often misunderstood character of John Dee emerges from the aeons, not as a madman, but as a brilliant and articulate architect of empire, whose spiritual practices compelled him to try and forge a new, kinder world from the ashes of the old. The American Empire, as it stands today, could do well to take a few lessons from his book.

**************

For more on Egan’s theories, visit his museum in Newport. Much of his research is available online as well.

For more on John Dee, check out Benjamin’s Wooly’s excellent biography, The Queen’s Conjuror.

For more information on John Dee’s influence on early colonial proclivities, check out W. W. Woodward’s Prospero’s America: John Winthrop, Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture, 1606-1676. I haven’t read it yet, but it’s on my list.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000038_00060]](http://theamericaneldritchsocietyforthepreservationofhearsayandrumor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Eldritch-Cover2-194x300.jpg)

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000420_00047]](http://theamericaneldritchsocietyforthepreservationofhearsayandrumor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Eldritch-Comics-01-Cover-212x300.jpg)