Challenging the general consensus that all giants are brutish, irredeemable rascals, Eunice Barnard Fuller’s The book of Friendly Giants (1914) mines folklore and ancient mythology as inspiration for tales of benevolent giants – although, she sometimes rewrites the pagan or otherwise esoteric source material in order to pursue her gentle agenda. Nonetheless, it’s a well curated tour of the mythology of giants; age-old Chinese, Norse, Celtic, and Native American stories are incorporated among more recent giant literature, such as “Gargantua and Pantagruel,”, a 16th century pentology of novels, or the 1887 book Three Good Giants, which introduces the primordial Chalbroth and his grandson Hurtali to the canon. The Friendly Giants stories culminate in a final, original chapter titled “The Giant Who Came Back,” set in 20th century New York City. It’s a nostalgic tale featuring the behemoth Benevaldo, who discovers that his people can no longer be seen by the humans that don’t believe in him.

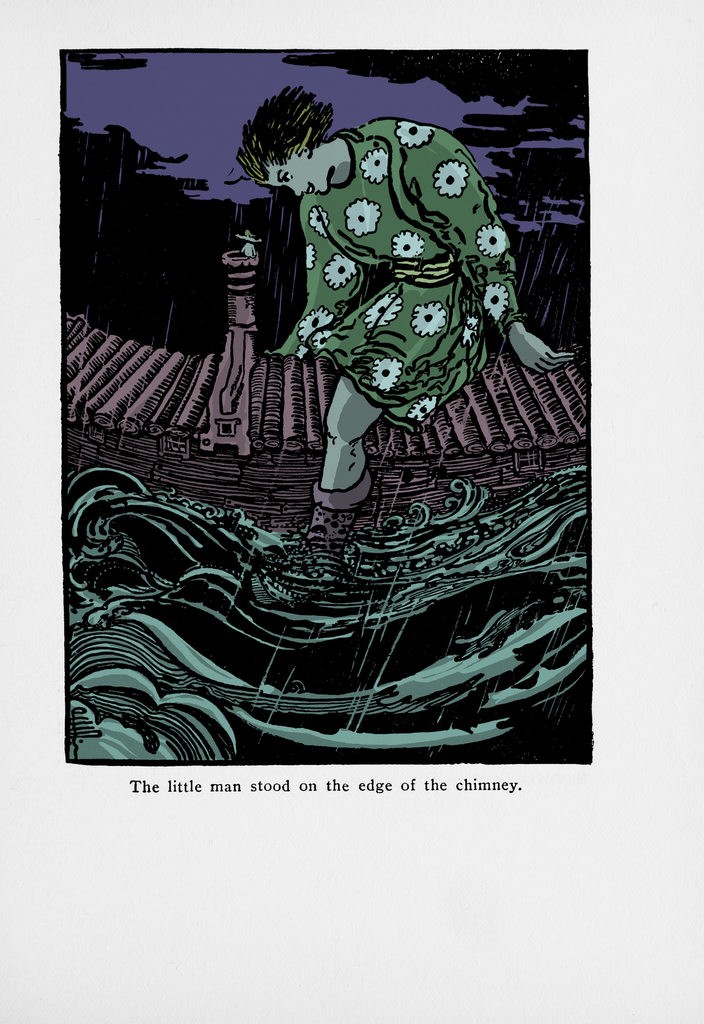

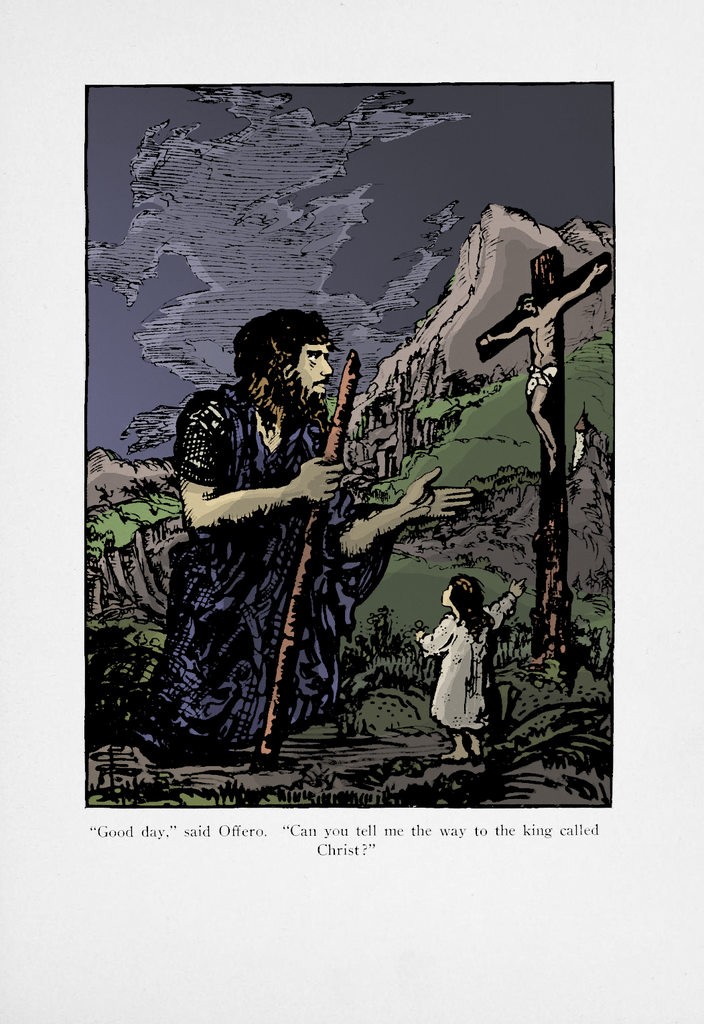

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith for the Book of Friendly Giants, 1914. Color by Aladdin Collar, 2016.

Each chapter is accompanied by a different introductory poem by Seymour Barnard, Fuller’s husband. I don’t care for his verses, and I’m glad he’s dead.

Bringing the text to vision, the infamous Pamela Coleman Smith (illustrator of the Rider-Waite tarot) provides what might be her final contribution to children’s literature (previous works of hers include The Russian Ballet, In Chimney Corners, and Annancy Stories). The illustrations fluctuate between simple cartoon art and fully painted scenes of fantasy and spectacle; her line-work is thick and rough, which especially serves the darker, more contemplative moments throughout.

While Smith is fairly well known, I was discouraged, upon examination, to discover that biographical information about Eunice Fuller is scant. I was curious what these two women had in common, and if Fuller shared Smith’s background in the occult order of the Golden Dawn, or any associations with A.E. Waite and his crowd. As it turns out, Fuller seems to have been a pretty dedicated Christian protestant (at least in her youth), and at the time of their collaboration, Pamela Coleman Smith had abandoned her hermetic interests and committed herself to Catholicism in 1911.

In continuing to research Eunice, however, I was encouraged to discover that she grew up in Lovecraft’s Providence, around four years his elder, a mere fifteen minute walk from Howard’s house on Angell st.

Eunice Fuller lived at 170 Prospect st, in Providence, Rhode Island (picture above, in 2015). She was born ~1886. From a young age, she proved herself to be a talented writer; records of her achievements can be found in volume 96 of the Missionary Herald in 1900, where Eunice was awarded second place in a Missionary Essay Contest for young writers, earning her $10. Regarding the contest, the Herald muses:

In 1903, Eunice took first prize in a fiction contest in St. Nicholas Illustrated, volume 31. $5 prize, and they published her full story. Later that year, her name appeared in Love and Life for Women, another missionary publication, as a record of Eunice’s junior auxiliary membership into their society.

In High School, Eunice was a member of the Upsilon Sigma Society, a theatre group that produced several original farces. Eunice played Jonas Chorker (the gardener) in “My Cousin Timmy” (1903), and she played Dandelion in the Clancy Kids (1904).

In 1907, after she’d graduated, Upsilon Sigma produced an original farce by Eunice and Margaret Courrier Lyon titled “A Visit from Obediah: A Farce in Two Acts (For Female Characters Only)”. Three other Fullers are listed as actors, and I am presuming they are Eunice’s sisters and brother.

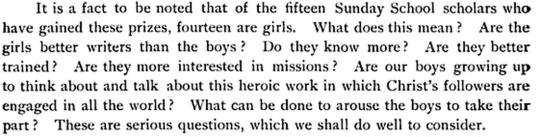

Eunice attended Smith College, and received a BA in 1908. She was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, and served as editor for the Phi Kappa Psi Society. She was a senior member of the Philosophical Society, and during her final semester, served as the President of the German Club (Der Deutsche Verein). Her 1908 yearbook is here, and includes the only picture of her I was able to find.

After graduating college, Eunice married Seymour Barnard, and worked primarily as a journalist, and an author of non-fiction. She wrote about American history, culture, economics, and women’s issues during the great depression. Her work appeared in Scribner’s, the New York Times Magazine, the North American Review, and more. Seymour, meanwhile, was published a couple times in the New Yorker, and he was fortunate enough to have one of his insipid poems illustrated by the illustrious Richard Scarry for Women’s Day.

The Book of Friendly Giants was published in 1914, to favorable reviews from various literary magazines; The Bookseller (vol 41) calls the volume a ‘new idea,’ whose ‘manner of telling is delightful,’ and praised Smith’s illustrations as ‘queer, funny and fanciful as one has a right to expect’. St. Nicholas published one of the 12 stories, with Coleman’s illustrations accompanying, and also a review that begins:

“Who isn’t interested in giants? But most giants are a bad lot, and the business in hand is how to kill them off without getting hurt yourself. But here in this book, the giants are quite a new sort…”

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith for the Book of Friendly Giants, 1914. Color by Aladdin Collar, 2016.

In the Worthwhile Reading section of the Independent (vol 80), a reviewer suggests that “After reading the book, the nursery will have to revise opinion regarding the viciousness of giants.” They did indeed; The Kindergarten-Primary Magazine reviewed the work, and called it “An excellent idea… a book the children will rejoice in.”

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith for the Book of Friendly Giants, 1914. Color by Aladdin Collar, 2016.

In the spring of 1929, Eunice opened a brokerage house just for women. I’m not sure how well that worked out for her out in the end, considering the timing, but it was a noble effort.

“So WALL STREET has come to Fifth Avenue. Silently one by one among the smart specialty shops of the Forties and Fifties appear the brokers’ signs. With the arts of the drawing room, stock market operators for the first time in history are actually bidding for feminine favor. And woman is at last being made free of those more or less green pastures where men long have dallied.” – Eunice Fuller Barnard, “Ladies of the Ticker,” North American Review, 1929

Ultimately, most of Fuller’s life and times are lost to the immemorial past; most of her imprint exists in her journalistic endeavors, which have been widely cited over a century of research and academic endeavors. At the very least, Fuller left behind enough evidence behind to prove that her obscurity is a disservice to our American heritage.