A VISIT TO THE MUSEUM

Newport, Rhode Island; Easter Saturday.

I just missed an egg hunt in Touro park. A few children still remain, playing, running between the statues and monuments that adorn its eastern end. There’s a chill in that air that should burn off by noon; the sun is just beginning to pierce through the misty morning grey. None of the lingering participants or their parents seem to pay much attention to the ancient stone tower that looms above the scene, the namesake of the road on which I walk; a crude-looking stone structure that Benedict Arnold[1], the first colonial Governor of Rhode Island called, “My stone built windmill.”

On the other side of Mill street, a few humble little storefronts face the park. There, nestled between a boutique clothing shop for kids and a nonprofit sailing organization for the disabled, the establishment that has drawn me here: the Newport Tower Museum. Its white-paned front windows are partially obscured by folding shades within.

The museum is the central hub of a story, one that I like very much, and the man who tells it waits for me inside.

“You must be Aladdin,” he greets me upon entry; Jim Egan rises from his seat behind the counter. He’s a gregarious man, more often grinning than not, with a booming voice that would be well suited for a lecture hall or a Vaudevillian chalk-talk circuit. We’ve only had a brief email exchange prior to our meeting, but I feel like I know him well from the videos I’ve watched online.

All around us, Jim’s research adorns the walls; the culmination of decades of personal investigation into the Newport Tower, its origins, its architecture, the secrets it hides. I’m well acquainted with the material, as Jim’s posted the bulk of it online, in various PDFs and video essays.

Here, the images and captions are transposed, reformatted, right from the pages of his books into picture frames. Their narrative is structure in the sequence of Jim’s own experience, from his initial interest in the tower all the way down the rabbit hole in which he found himself, leading to a rather unlikely suspect.

Last night I was up late, arguing with skeptics online regarding the plausibility of Jim’s theories. I didn’t change any minds.The evidence overwhelms me; I’m no historian, no astronomer, no cryptographer. Still, I find all of those subjects fascinating, especially in the context of this enigmatic American ruin.

The whole ordeal is driving me a bit crazy, because I think Jim’s on to something. If his assessment is correct, it would mean that theTower is the very first structure built by the English on American soil, preceding Roanoke, preceding Plymouth Rock. But, Jim’s books, his museum, remain profoundly obscure; his ideas have not disseminating into popular consciousness.

I’d never even heard of the Tower until last year, and Jim’s theories are so esoteric that Wikipedia doesn’t even include them within its “alternative hypothesis” section on the Newport Tower page (which does include debunked theories, such as the Chinese, the Portuguese, and the Medieval Templar origins for the structure). But, the more I read into Jim’s research, and the sources from which he draws, the more it makes sense.

I’ve been looking for holes in the story, but, like a toy finger-trap, it gets stronger as I struggle against it. In that respect, perhaps Jim is the last person I should be talking to if I want to regain control of my life, and stop falling into late night fringe-history binges.

Nonetheless, on this lovely spring morning, I have come to the Mecca of my curiosity, and Jim Egan is the prophet with whom I must reckon.

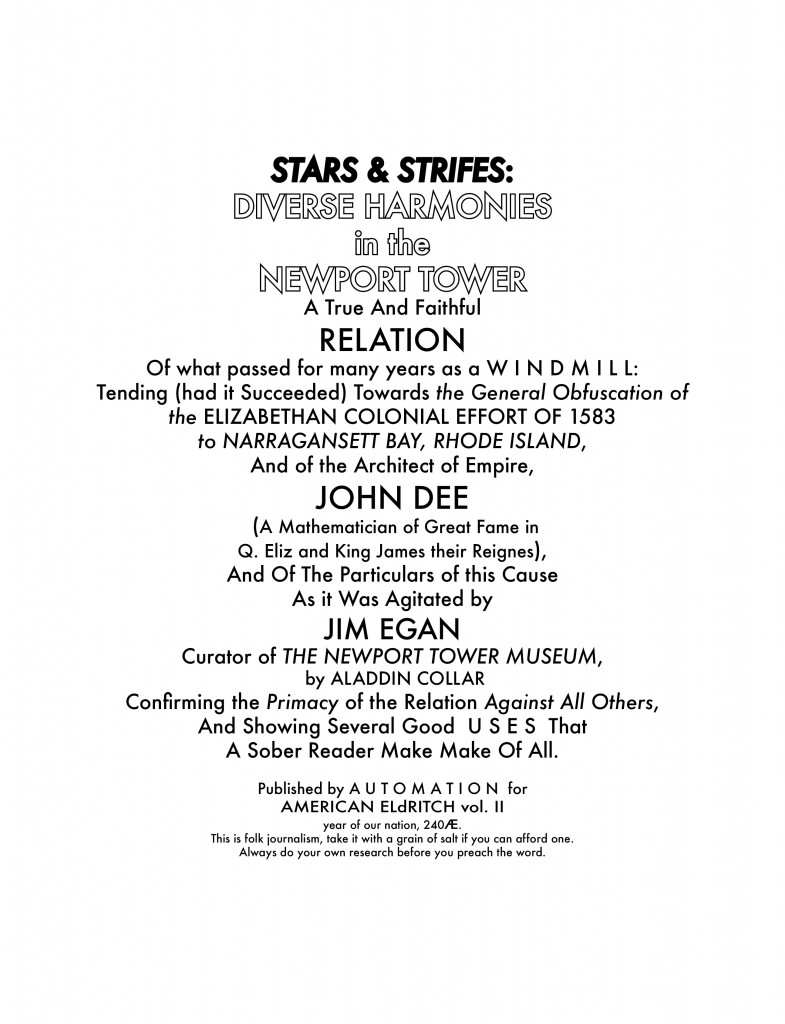

ARNOLD’S “MILL”

“There are very good reasons why [Arnold] called it a windmill,” Jim explains, when I ask him to defend the premise that the Tower was not built to mill. “If he told people what he knew about who really built it, the Elizabethans, then the families that built it would come here and say, ’this is our tower, this is our land, you guys gotta screw outta here.’”

Indeed, Arnold was the first English settler to stake a claim on the land that would one day become Touro Park, in Newport, Rhode Island. Although no biographies have been published about the Governor, Jim has written extensively about him, culling research from the innumerable tomes he’s collected in the Museum’s library.

Benedict Arnold and his family settled in the area, acquired vast tracts of territory, and established trade routes all along New England, using the Narragansett Bay as their new port of commerce. Arnold was a shoe-in for Governor, selected by King James I. As the Rhode Island colony grew, Arnold was re-elected to serve 12 years in office. Between Newport and Providence, the Rhode Island colony became a hub for intellectualism and philosophy, without all the auto-flagellation and witch-hunting that was so popular in Massachusetts (Puritans, aren’t they just the worst?).

“He’s totally ignored in Rhode Island history,” Jim notes; Arnold’s great-great-great grandson turned out to be a real piece of shit during the Revolutionary War, and the American public at large doesn’t look kindly on traitors, or their families. Few people have ever heard of him.

Still, Arnold the First left behind letters, legal documents, and all the political discourse and action recorded during his tenure as a politician. The remarkable Tower is invoked only in Arnold’s will, as necessitated by his impending death. His ‘stone built wind mill’ was bequeathed to his wife, Demaris, to be then given to his daughter, Freelove.

“Here’s the problem,” Jim tells me, vexed by the greatest obstacle his theory faces, that four-word phrase. “There are academics who see the will, and read the will, and the fact that it says ‘stone built wind mill,’ that becomes what they call ‘primary evidence.’ And they don’t look any further than that – they don’t see that maybe there was some ulterior motive, maybe something else going on.”

HISTORY OF THE MYSTERY

As far as New England colonial architecture is concerned, the Tower is a curious example, because there’s simply nothing else like it[2]; surely, during a time when resources were fairly limited, an auspicious building project like the Tower would have been the subject of some discussion? This question was first raised by Danish antiquarian Charles Christian Rafn in 1839: “The singularity of erecting such a unique piece of architecture, at such a time, would have been noised far and wide throughout the Colonies.” We know that the first windmill in Newport was built by Peter Easton in 1663; why do no such details remain of its much more notable successor[3]?

Rafn suggested that the Tower was actually built by vikings in the 12th century, and then retrofitted as a windmill by Arnold – a claim that was hotly debated, and generally rejected by scholars and historians. Rafn’s theories nonetheless prompted an influx of tourism, pop journalism, and even a romantic ballad by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called “The Skeleton in the Armor.” A nordic aesthetic helped inform the small city’s 20th century identity; amid 17th century colonial architecture and the subsequent Gilded Age mansions, the Newport grand hotel is called The Viking, and the city’s high school mascot is a Viking as well.

Over a hundred years of investigation would strongly suggest that the Tower is not an artifact of pre-Columbian transatlantic contact[4], but is colonial American in origin. To its investigators, there were but two possible origins for the tower: a Viking Tower, or, Governor Arnold’s Mill. Sober historians saw no evidence to implicate the former, and the academic consensus was agreed upon: it was just a windmill. Nothing to see here, folks; move along.

THE STARS ARE RIGHT

In the 1990’s, professor William Penhallow (of Rhode Island University) decided to investigate an old rumor that had been circulating among viking enthusiasts. It was an attempt to explain the bizarre placement of the windows; despite the symmetry evident throughout the rest of the structure, the windows are irregularly spaced in defiance of the arches and intercollumnation. That architectural choice follows no known model or tradition[5], but Viking theorists postulated that the windows were situated in such a way as to provide a specific view of the stars.

There are a few specific locations in Touro park from which you can see between windows. In these spots, the focal point cannot be changed, and the view from one window through the next represents less than one percent of one percent of the total night sky. Were any significant cosmic movements visible from these specific vantages? Penhallow used a computer simulation to look.

He found that one such alignment provides a glimpse of an extremely rare astronomical event, the minor lunar standstill in full moon, reoccuring every 18.6 years. It’s the only time the moon ever passes through those windows at the same time. An improbable number of significant alignment predictions followed, as Penhallow examined the Tower from within and without.[6] The sun only aligns through the Southern and Western windows once a year, he found, precisely on the winter solstice.[7]

Many critics maintain that the alignments are meaningless; the result of random chance. In the chaos of natural law, little to no chance is provided for all of these elements of diverse harmonies to converge; even the first spark of primordial life on earth demanded fewer conditions be met. So…

“What could the purpose of the tower be?” Penhallow muses at the conslusion of his paper. Although he does not purport to be a historian, he offers his own theory. “Possibly to provide the necessary information to determine the proper times and dates of religious observances. A religious building of this kind could have been the focus of activity for a group of Europeans seriously intent upon colonization since it represents a considerable expenditure of time and effort.”

That was precisely what Jim Egan found.

“Professor Penhallow and I have been studying the tower for over thirty years now,” Jim explains, as he indicates towards a framed photograph of the Newport Tower, with the moon gleaming through its windows on December 3rd, 1996.

Before he was the curator of the Newport Tower museum, Jim was a professional photographer. Following Penhallow’s report, Egan began diligently documenting and verifying each of the proposed alignments in film, and, compounding the project with research and experiment, he correlated a few otherwise minor events in the historical record with the Tower, providing a new context in which this strange astronomical Tower could have plausibly been erected. Jim’s confident enough in his solutions to have left his other commercial pursuits, purchased the property across from the tower, and opened his museum to the public.

To Jim’s great misfortune, however, the architect that he’s identified is none other than John Dee (above, right), an Elizabethan polymath, astrologer, and alchemist, perhaps best known today for his pursuits in spiritualism. Fringe history that delves into the occult? The academic response has been quiet[8]. “They stay away in droves,” by Jim’s account.

I ask him about the reaction from the town. “Have you had people who’ve lived here all their lives that came in and said, ‘Oh, this suddenly all makes sense to me?'”

Jim pauses, and a contemplative look curls into a grin.

“No,” he replies, and laughs.

” When I first opened up, I asked all the historians in town to come visit my museum. The head of the Newport Historical Society, the librarian of the Newport Historical Society – they came, they spent about 20 minutes here, and they’re like, ‘Nah, we don’t think so, doesn’t fit with anything that we know.’ And they just let me be.” Egan shrugs. “I’ve invited people from the Redwood Library, the Rhode Island Historical Society, the Rhode Island Historic Preservation Society in Providence.”

While a journal published by the the American Eldritch Society for the Preservation of Hearsay and Rumor won’t bring Jim any closer to academic credibility[9], I will say that I have ordealed to present the facts in the case without hoax or deceit. I cannot endeavor to include all alternative research and hypotheses, I have seen fit to include major arguments, where I can, to the contrary of Jim Egan’s marvellous tale.

TO BUILD A STEADFAST WATCHPOST

Glindoni, Henry Gillard, 1852-1913; John Dee Performing an Experiment before Elizabeth I. This painting was recently forensically examined, and it was determined that the artist originally included a ring of skulls around John Dee.

Throughout all of the theories that have been projected regarding the Newport Tower, no one but Jim seems to have considered that John Dee and the “heroic” explorer Humphrey Gilbert[10] had planned a colony around Narragansett Bay. It would have been the first settlement of the burgeoning British Empire, and a base from which to explore the New World for the Northwest passage, a fabled trade route upon which both Dee and Gilbert hoped to capitalize (they never did, and the passage wouldn’t be discovered until 1850).

Jim stumbled across their endeavor while researching historical names for the Narragansett Bay; in the 1580’s, before the English had ever arrived, it was known as the John Dee Bay and River.

“I was like, this is huge,” Jim recalls. “An effort to colonize the new world – here’s a building that nobody knows who built. Well, that was just the beginning of my exploration.”

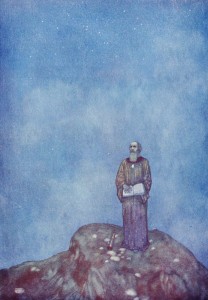

The Colony at Dee River ultimately failed; Humphrey Gilbert set sail in 1583, with five ships of settlers, but due to disease and bad weather along the way, a lot of people died, including Gilbert[11]. Dramatic accounts from the survivors were popularized in literature; Egan suggests that Gilbert’s shipwreck was an inspiration for Shakespeare’s Tempest (which falls in line with a popular suggestion that John Dee inspired the character of Prospero).

Prospero, by Edmund Dulac, 1915. “And by my prescience, I find my zenith doth depend upon a most auspicious star.”

Until the 1930’s, no one actually knew where Humphrey Gilbert’s colony was going to be. The answer was hiding in the Elizabethan state papers; a deed for the colony was extant, and was discovered by Rhode Island historian William Goodwin. The deed describes the location of the colony, the general structure of the government, and the parcelling of land. To John Dee is awarded the the whole Bay, as well as 1.5 million acres of land to its west; that parcel contains the land on which the Tower currently resides.

Another recipient of vast tracts of land is George Peckham, who was one of the wealthiest Catholics in England. After being convinced by Dee[12] that their colony would not infringe on Spain’s territory, Peckham helped to bankroll the colonial efforts, and, if Egan’s theories follow, he likely paid for the Tower.

Prior to his final star-crossed voyage, Gilbert sent two reconnaissance missions across the Atlantic; one in 1580, with a single vessel, gone for three months, and then another, in 1582, with two ships, and a smaller boat. No one knows for sure what the second expedition did while they were gone, but Jim boldly asserts they were deployed to construct the Tower, according to plans drawn by John Dee. Jim presumes it to have been built as a house of worship in compliance with Dee’s Renaissance ideals, in order to greet the incoming settlers and establish an Empire for England.

“These two ships,” Egan highlights, “About 80 men, they came here and they stayed for 9 months. We know that they returned to England because Brigham, the leader of the expedition, talked to Sir Francis Walsingham about ‘the discovery of America.’ Now, the ‘discovery’ didn’t mean ‘We’re finding it,’ it meant, ‘the settlement of America.'”

In a letter to his King, the Spanish ambassador and spy Bernardino de Mendoza reveals why the destination of England’s first New World colony was such a well kept secret: “Through the [Catholic] clergy,” the spy writes, “I have made known that those lands belonged to your majesty, that we had garrisons and fortresses there, and that they would immediately have their throats cut as happened to the French who went with Jean Ribault.”[13] Although the Spanish were principally concerned with Central America and Florida, the English knew that they risked war by encroaching on the New World territories.

Dee’s contributions to the colonial effort cannot be understated. The whole argument for colonization, and Elizabeth’s patent to Gilbert, rested on the legal framework that Dee himself had developed. He wrote eight treatises on the subject, which he presented to the Queen over the course of two years (1776 – 1777). His arguments concerned mythology, the supremacy of King Arthur, and the rights of first discovery by Madoc, a heroic Welsh prince from the 12th century who was reputed to have settled in America[14]. Dee also poked holes in legal language used by Papal land agreements between Portugal and Spain; no nation had laid claim to the greater North American continent, and should Elizabeth manage to occupy, she was dutifully obliged to Christianize the land. Dee convinced Peckham of this in 1582, as recorded in his diary[15].

Occupation was a major part of Dee’s legal framework; Neither Dee, nor Gilbert, nor Peckham would be awarded their land patents without establishing a physical presence.

“Send forth a sailing expedition…” Dee writes in Greek on The Hieroglyphicon Britannicon, the frontispiece to Rare and General Memorials. “…to build a steadfast watch-post.” A small detail on the page offers evidence that round, pillared Towers were in fact a component of Dee’s colonial vision (and, evidently, not as windmills).

A NEW ORDER FOR THE AGES

With the details of John Dee’s colony scattered over so many years and a few relatively obscure books, I’m not too surprised that Jim Egan was the first to arrange the pieces in such a way as to implicate the Tower. But there it stands: a Medieval-looking ruin in the midst of New England. Could such things be?

Dee is not known to be an architect; however, as an accomplished polymath, it isn’t infeasible that he could have drawn designs for such a structure. Dee owned numerous volumes on architecture, and he wrote on the subject as well, translating from Vitruvius and others in order to extoll the virtues of an art he identified among the mathematical sciences.

” Architecture, is a Science garnished with many doctrines & diverse instructions,” Dee writes, in his Mathematical Preface to the first English translation of Euclid’s Elements. He goes on to state: “The architect must know the East, West, South and North, and the design of the heavens, the Equinox, the Solstices, and the course of the stars.”

That philosophy can be found in a very literal way in the Tower. The pillars on which it stands are arranged to the compass rose[16]. In addition to the unlikely exterior window alignments with the winter solstice and the lunar solstice (the standstill), Penhallow has identified window alignments with stars Sirius and Dubhe. Inside the tower, during the sunset of either Equinox, the warm falling light spills into the recession of the fireplace[17].

Dee was an astrologer, and advised on important dates and times[18] by consulting with the heavens. Astrology led to horology when Dee was tasked by Queen Elizabeth with the design of a new calendar, at the advent of the Gregorian Calendar Reforms. Dee calculated his year based on camera obscura sun disc observations (the same way that Pope Gregory’s horologists had drawn the Catholic maps of Time).[19]

It was to that effort that Jim Egan thinks that Penhallow’s “calendar temple” owes its cosmic machinations. Jim asserts that John Dee’s ventures were all connected, and that the Time Keeping Temple supported his proposed Reformation of the Vulgar Julian Year.

“He draws this thing called the Circle of Time,” Jim explains, describing a diagram from the Calendar proposal. It clocks all of human history (at least, according to Dee). “Adam; Enoch; Noah; Abraham; Jesus Christ; the very last one is Queen Elizabeth the reformer of the year for the next Christian epoch – and that’s to begin in 1583.”

Jim raps his hand against the wall three times to punctuate the effect of that harmonious date.

” So the Tower is not only representative of this new time, but also of the birth of the British Empire (which later became the largest empire the world has ever known).”

NO EASY PARADIGM SHIFT

“You should have been here about an hour ago,” Jim tells me, glancing out of his window. “They had, in this park, at exactly 10 o clock, 150 children, 150 adults, and they put these plastic eggs – 2000 of them – all over the park. At exactly ten o clock. An easter egg hunt. The kids came and picked up all the eggs – they had the easter bunny here. A fire truck. This place was crazy. And then, as soon as they leave, they come and picked up all the eggs, now there’s not one of them. It was just like, the most colorful scene this morning. There were all these hundreds of people here, and no one even looked at the Tower.”

Jim’s long-term ambition is to convince UNESCO to classify the Tower as a World Heritage site; his short term ambition is simply to spread the good word of John Dee. To that end, he’s lectured at libraries, conferences, masonic halls, and TedX events; wherever a curious audience presents itself, Jim is there to amaze and astound.

At the conclusion of my tour, Jim offers me some light reading to take home; seven of his books, and a copy of his favorite biography on John Dee[20]. I try to politely refuse the latter, but he has a dozen of them; whenever he finds a used copy, he buys it, to spread the good word.

I am overencumbered by the volumes of information. It’s a recursive trap, one that I may never escape; without any firm evidence emerging soon, the mystery will persist.

Like the haunted video tape in the Ring, I pass the curse on to you; every avenue of Jim’s story that I explore has yielded boundless excitements, and I encourage you, dear readers, to follow suit. I have only been able to provide a brief overview of the full thesis that Jim’s prepared – I didn’t even get to the Monas Hieroglyphica, John Dee’s most cryptic work (which Jim Egan has newly decoded), or to the whole Easter pagent that would appear to play out through the Tower’s solar displays. The Museum, however, and its accompanying website, hold all of those stories, and many more.

While the academics ignore him, the artistists are moving in on Jim’s marvelous tale. Outside of the main exhibit, Newport Tower fan art hangs on the walls; images such as that of John Dee, transposed against the tower. A recent fantasy novel, Newport Knights, by H.B. Loomis, features Jim as a Merlin-esque figure, guarding secret magical wisdom of the past.

“Artists, painters, sculptors, and they get it,” Jim says. “They’re creative thinkers. They live outside of the box. To think of an idea outside of the box isn’t hard for them. But for historians, I’m afraid (and I’m not dissing them)… it’s just the way they are. They’re librarians. Their job is to keep things in boxes, in the right box, in the right place, and if you’re out of the box: we’ve got to bring you back in.”

But, Jim won’t go.

“One guy trying to change the paradigm – what a silly thing. At first I was optimistic, I was like – I can do this. I can change the world. Well, that shit doesn’t happen. It takes years – groups, lots of people. It doesn’t discourage me at all, that’s the way it’s gonna be. That’s the way it is. ” Ӕ

[1] Not that Benedict Arnold; his great-great-great grandfather.

[2] Skeptics will indicate towards the Chesterton Windmill, which sits on six pillars and arches in England, built in 1615.

[3] In the known historical record, there is but one third-hand account of the Tower’s potential use as a mill, an 1834 deposition signed by Newport native Mr. Joseph Mumford. The deposition states that “[Mumford’s] father was born in 1699 in said Newport, and that his father always spoke of the Stone Mill in this town as the Powder Mill… His father used it as a hay-mow — that there was a circular roof on it at that time and a floor above the arches — that he has himself, when a boy, repeatedly found powder in the crevices, sometimes to the amount of two or three pounds, and has likewise known other boys to find quantities of it.” (Brooks)

[4] Multiple archeological digs have been performed in Touro park, and the grounds have been scanned for anomalies. No artifacts or relics have been found that would indicate a European migration that predates the English settlers.

[5] The architect George C. Mason attributed the window placement to the mechanics of the windmill itself, although his model of comparison, the Chesterton Windmill, does not follow this design.

[6] Archeoastronomy is generally considered a dubious science, and it’s also not Penhallow’s field of specialty. He is a professor emiritus of Rhode Island University, and taught physics, math, and astronomy.

[7] Since his research was conducted, an autumnal solar alignment has been discovered as well, further compounding the unlikelihood of coincidental alignments.

[8] Jim was featured as one of several luminaries in a cheesy History Channel special, America’s Oldest Secret, which you can find on youtube.

[9] For example, the museum we visited last issue, the Natural History Museum of Cryptozoology, doesn’t even exist. This one does, I promise.

[10] Gilbert’s actually a trash-ass nasty boy; he regularly decapitated Gaelic Irish villagers (men, women and children) as a measure of social control in the late 1560’s, and rumor has it his colonial plans included a Native American genocide.

[11] See the Death of Humphrey Gilbert gallery that follows. It doesn’t have much to do with the overall story here, but I think Gilbert was horrible, and I relish in his death.

[12] Dee’s Diary: July 3rd. A meridie hor. 3½. cam Sir George Peckham to me to know the tytle for Norombega in respect of Spayn and Portugall parting the whole world’s distilleryes. He promysed me of his gift and of his patient…. of the new conquest, and thought to get so moche of Mr. Gerardes gift to be sent me with scale within a few days.

[13] Jean Ribault, an influence in Gilbert’s early colonial interest, was the leader of the French Huguenots settlers that were brutally massacred by the Spanish in Florida (1564).

[14] Though he was an early Madoc devotee, the folklore preceeded Dee, and evolved well beyond his telling; the prince is said to have built his fortress upon the Devils backbone, outside Louisville, KY (per Margaret Sweeny’s 1967 Fact, Fiction and Folklore of Southern Indiana).

[15] ” A meridie hor. 3 J cam Sir George Peckham to me to know the tytle for Norombega in respect of Spayn and Portugall parting the whole world’s distilleryes. He promysed me of his gift and of his patient of the new conquest…”

[16] They are technically off the cardinal directions by 3 degrees.

[17] Egan conjectures that a camera obscura would have been employed in the window, projecting an inverted image of the “fiery water” of the Narragansett Bay at sunset directly into the fireplace. The effect only works on the first day of Spring, and the first day of Fall.

[18] Such as the cornonation of Queen Elizabeth (January 15th), or the date of departure for Gilbert’s fleet.

[19] Like the Dee River Colony, Dee’s calendar project ended in failure, in the very same year, 1583. The proposal was rejected by the Church of England on political (religious) grounds, and England’s calendars were 10 days off for the next two hundred years (idiots).

[20] The Queen’s Conjuror, by Benjamin Wooly, 2001.